I’ve written about metastable failures before. The topic has been picked up by a few different teams since the, all analyzing metastable failures more, while I apparently has been slacking off… Anyway, Metastable failures are self-sustaining performance failures that arise in systems due to a positive feedback loop triggered by an initial problem. This positive feedback loop, or as I sometimes call it, a sustaining effect, is the defining characteristic of the metastable failure pattern. If we can somehow stop the loop, we stop the self-sustaining part, making recovery from the initial problem much easier.

Actions, States, and Signals

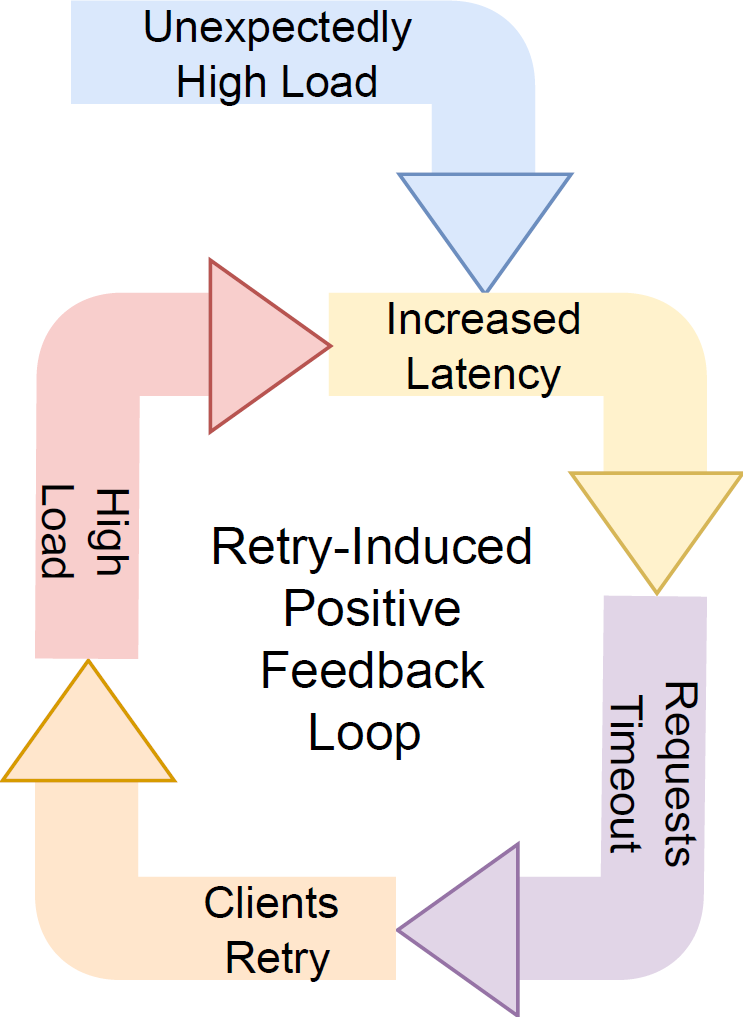

To better understand the problem, we need to examine the feedback loops. A typical metastable failure example is a retry storm: a serving system is overloaded due to an initial problem, the overload leads to high latency and timeouts for some requests, and clients retry those timed-out requests, creating even more load, higher latency, and even more timeouts and retries. In this scenario, we have two systems that interact with each other: clients and the serving system.

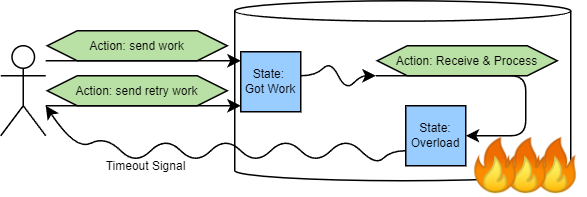

The two systems are in a control loop that has positive feedback. Under normal conditions, a client acts by sending some requests. These client actions change the state of the serving system, as it now has work to process. This state change produces a signal for the serving system to act by receiving and processing requests. Receiving and processing requests also changes the state of the serving system in many ways. One that interests us is the load on the serving system. The load state produces signals that clients can observe: request latency and request timeouts.

Here is the crux of the retry problem, though: we do not want to retry when the serving system is overloaded. We want to retry when there is an intermittent failure, such as a message loss, a server failover on the serving system, or any other short-lived failure. These failures, however, send the same signal to clients, as the overload state: request timeouts.

Going back to metastable failure, when the serving system slows down, the load increases, and this state produces request-timeout signals, the clients act on those signals and retry some work. It is this action performed erroneously on an ambiguous signal that causes the serving system to receive more work, become even more loaded, and produce a stronger request-timeout signal, completing the loop.

In short, we can explain interactions as follows: systems or components observe signals and act on them by interacting with other systems/components. These interactions change the state of the components, which emit new signals that can be acted upon. While signals are proxies for some state of a system or component, they are often ambiguous — different states may produce the same signal, and different systems or components may produce the same signal.

Avoiding Metastable Failures?

In the intuitive model described above, there are a few ways to avoid metastable failures.

Avoid interactions between components. These interactions provide input/output to/from systems, and “interesting” programs tend to both need input and produce output, so altogether avoiding them is not an option. However, minimizing unnecessary interactions is a good mitigation strategy.

Avoid taking actions that create positive feedback. This strategy is also easier said than done. Our retry feedback loop example has four distinct actions: clients can send and resend requests, and the serving system must receive the requests and then process them (well, reply to the client too, but we can “wrap” it under processing here). This example also includes several signals: the work arrival, which triggers receive and process actions, and the request timeouts, which trigger the resend action.

Some of these actions are “forced” upon the system. A serving system generally cannot skip the “receive” action — as packets arrive at the machine, it will use resources to get those requests from the network and maybe even parse them, affecting the load state.

Some actions are semantically important and “forced” by the utility/usefulness requirements. A serving system that does not take a “serving” action is useless (and will run out of memory receiving all the requests and doing nothing with them). Similarly, a client system that does not take action to send requests is not very useful. The serving system can have a drop-request action to avoid doing work. However, this action can only be taken after receiving the request (which already impacts the “system load” state). Furthermore, we cannot take this action all the time, so we must use some signal to decide whether to take the “serve” or “drop” action after receiving the request, further complicating the system with additional interacting components.

This leaves us with a retry action. We can surely avoid taking it. But this has side effects. Without retries, the system also won’t handle minor transient problems as gracefully.

Finally, some algorithms “force” certain actions that, by design, create positive feedback loops. For instance, distributed transaction protocols, such as Two-Phase Commit with Two-Phase Locking, have a contention state. When many transactions need the same key or object, some may wait longer to acquire a lock, and some may abort and retry. The algorithm prescribes both actions (wait and abort). And both actions ultimately result from the same signal: inability to acquire locks (which occurs in the high-contention state). Crucially, taking these actions actually increases contention: either the transaction waits for longer and has a higher chance to contend with other transactions, or it aborts and retries, which has the same “stay longer and interfere” impact in addition to redoing some work. And these actions cannot be removed without either correctness or liveness implications for the algorithm.

Avoid ambiguous signals. Recall that the problem we have with retries is the inability to distinguish between the faults that retries can fix and faults that retries amplify because both produce the same signal.

Making signals unambiguous is hard, but it will ultimately allow us to take the right actions (or inaction) in the right situations. It may be a good idea to rely on multiple signals to activate an action. For example, if signal A can indicate problems x and y, and signal B can only be produced by issue y, then activating an action to deal with issue x requires both signals A and B.

In case of retries, things get complicated, since the signal we use is the “nothingness” we get from the system. The timeouts, or the absence of a reply, indicate that something is wrong, but cannot provide any additional information about what is wrong to disambiguate.

Mitigating Metastable Failures Instead of Avoiding

Fault-tolerance is hard, and in the case of metastable failures, maybe next-to-impossible and/or expensive. I have a hunch that we may not be able to avoid metastable failures entirely in large, non-trivial systems that are also economical to operate, because of these “forced” actions that systems sometimes have to take. However, the three strategies above remain effective mitigation approaches. Just replace “avoid” with “avoid as much as possible.”